|

An Introduction to Web Browser Privacy & Security The Basics To protect your privacy and security while browsing the web, you need to perform several basic tasks with your web browser, whether it be Internet Explorer, Netscape, Mozilla, Firefox, or Opera:

Many readers will not be familiar with these aspects of their browser or even how to perform these tasks, all of which are actually quite simple. To help you get started protecting your privacy and security online, this introductory page contains tips and info to guide you through the basic browser configuration tasks that you should perform. This page also points you to some readings on the web that explain why a user like you might want to perform these tasks. Although most major web browsers are substantially similar to each other in many respects, there are differences. Thus, it's important to know which web browser and what version you're using. All of the companion pages to this page (see below) contain instructions to help you figure out which browser version you're using. Most web browsers give you detailed version information when you click Help >> About from the menu bar. Companion Pages There are seven companion pages to this one to help you understand web browser privacy and security, no matter which of the major browsers you happen to be using. There are companion pages for:

Also, there is a separate page for AOL that covers preferences unique to that online software suite. (AOL users should read the Internet Explorer page as well, because the AOL web browser is really just Internet Explorer with a slightly changed face.) You can read those pages independently of this page, or you can move on to the introductions to each topic on below and then go to the appropriate sections of the companion page for your browser when you need more information. AOL Web Browser If you're using the AOL web browser, you are, in fact, using Internet Explorer underneath, even if you never realized it. On the Internet Explorer companion page, we'll show you how to find the version of Internet Explorer that your AOL web browser is relying upon as well as how to access privacy and security settings from within AOL. 1. Configure & Clear the URL History & Browser Cache (Temporary Internet Files) This is the easiest set of tasks to perform to protect your privacy and security. Both of these tasks involve deleting junk that your browser accumulates as you surf the web.

So, What's the Problem? If your browser uses a browser cache and URL history to help you find and return to web pages speedily and conveniently, why would anyone want to periodically clear the browser cache and URL history? Two reasons:

Terminology A short note about terminology: I've referred here to something called a browser cache. A cache (pronounced "cash," not "catch") is simply a temporary storage area. Computers use caches to temporarily store data until they can be moved to some other location. Your computer and its software use many different types of caches for different reasons (usually to improve performance). For this discussion of browser privacy and security, we'll be talking about one particular cache that your browser uses to temporarily store copies of web pages that you visit. That's called the browser cache. Internet Explorer doesn't use the term browser cache, however. It uses the term Temporary Internet Files instead. A browser cache and Temporary Internet Files are, in fact, the same thing -- they're just different names for the same cache. Clearing the URL History & Browser Cache All major web browsers allow you to clear the browser cache and the URL history separately.

More Info To get a better, more complete description of the URL history and browser cache and what they're used for, see these pages:

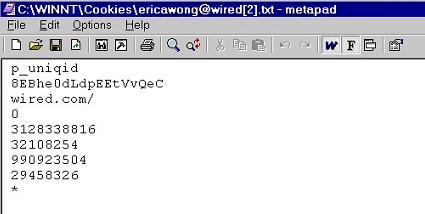

2. Configure & Delete "Cookies" Cookies are small "data tags" that store unique identifying information from web sites so that those web sites can recognize you when you return. In a sense, they're like name tags for your browser (but they don't literally have your name in them). If you've ever shopped at a web site and then returned at a later time, you probably noticed that the web site seemed to recognize you when you came back. They recognized you because the web site planted a unique cookie on your hard drive. You might have also registered with a web site so that you could view special content on the site; each time you returned to the site, the web site let you right in instead of forcing you to log in every time (web mail services like Hotmail or Yahoo! often do this). The web site could let you in automatically because it recognized you from the cookie it stored on your hard drive. What's in a Cookie? As I said, cookies are just small data tags -- chunks of information. They're actually quite small. Moreover, we can open up a cookie and look at the contents. Let's take a peek inside a cookie and see what's there. Here's a cookie that someone picked up from WIRED News while surfing with Internet Explorer:

Notice that there are three main types of information:

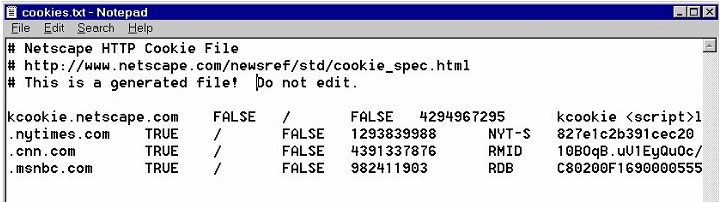

That's it. That's all a cookie is: a small amount of data that web sites place on your computer to help recognize you when you return to those web sites. One other fact about cookies is useful to know: Internet Explorer, as we saw above, stores cookies as individual text files -- one cookie per file. Most other browser store cookies differently, however. Netscape, Mozilla, and Firefox all store their cookies in a single file (named cookies.txt), which looks like this:

You'll notice that these cookies (one per line) contain the same information as the cookie we looked at above. Netscape, Mozilla, and Firefox cookies are the same as Internet Explorer cookies -- they're simply stored in slightly different ways on your hard drive. So, What's the Problem with Cookies? If cookies can be so useful (doesn't everyone want to be recognized once in a while?), why would anyone want to turn them off or delete them? The answer is simple: to protect one's privacy. We all like to be recognized in some situations -- being recognized can be convenient and helpful, such as when you return to a shopping site that you go to frequently. But we wouldn't want our behavior on the Internet to be tracked all day, every day, from web page to web page by advertisers and marketers. That would be like wearing a name tag all day long and going through your day, knowing that your movements and actions were being tracked and recorded for future reference. Imagine if someone tagged you at a shopping mall, monitored which stores you went to and what you bought, and then used that information to bombard you with junk mail, telemarketing calls, and advertisements. That's essentially what cookies allow advertisers and marketers and marketers on the Internet to do. Here's how it all works: web sites often partner up with advertisers like Doubleclick, which happens to be the largest advertising company on the Internet. Those advertisers place banner ads on the web sites that they partner with. And through those banner ads the advertisers attempt to place cookies on your system from the advertisers themselves, not the web sites you're visiting. Those kinds of cookies are known as third-party cookies: you're Party #1 visiting a web site, which is Party # 2, but that web site has advertisements placed by Doubleclick, which is now Party # 3, and Doubleclick places a cookie on your system. The cookie you get isn't from the web site you're visiting, it's from a third party that places banner ads on that site. Now, let's say you leave that web site and go to another web site. Guess what? That new web site also uses Doubleclick for banner ads, and Doubleclick will read the cookie that you picked up at the previous web site and recognize you as a visitor to that previous web site. And so it goes: Doubleclick (and other advertisers) can now track and monitor your visits from web site to web site, compiling data about where you go and what you do. That data about your behavior is valuable, because it allows advertisers like Doubleclick to target advertising directly at you based on your interests and activities -- that kind of advertising is known as direct marketing. It's also an invasion of privacy. You may not have ever heard about Doubleclick, but Doubleclick most certainly knows about you. If you've never deleted cookies from your hard drive, then you undoubtedly have at least a few cookies from Doubleclick, and they've been using those cookies to monitor your behavior on the Internet for some time, probably from the very first day you brought home that brand new computer, logged on to the Internet, and went surfing. More Info To learn more about cookies and why they're used by web sites, see these pages:

Privacy.net has even set up a few web pages to demonstrate what cookies are and what they can do: Dealing with Cookies To protect your privacy with cookies, you need to learn how to do two things:

You need to learn how to perform both of these tasks because different users will want to handle cookies in different ways. Some will simply want to turn cookies off completely. Others, however, will want to accept cookies and then delete some of them on a case-by-case basis, keeping a few cookies from web sites that they visit frequently. You may even decide to change the way you handle cookies at some point. If you know how to configure, manage, and delete cookies, you'll have complete control over your browser's use of cookies. All major web browsers handle cookies in slightly different ways:

3. Turn Off "Active Content" Features of the Browser Your web browser can not only view static text and images on web pages, it can also automatically run programs that are embedded in those web pages. Programs that are embedded in web pages are commonly referred to as "active content" to distinguish them from the "static content" of plain text and images. Active content -- programs that are part of web pages -- can seem like a strange concept, but if you've ever surfed the web, you have seen programs running within web pages (and perhaps not even realized it):

All those things --moving objects, popup windows, and animation sequences -- are driven by small programs that your browser automatically downloads from a web page and runs, just like your computer runs a program like Microsoft Word. (Note that in describing "active content" as "embedded programs" I'm not referring here to normal programs that you deliberately download and save -- these "active content" programs are different because they're actually loaded as part of the web pages you visit.) Active content is popular with web developers (the folks who make web pages) because active content like Java, ActiveX, and JavaScript enables them to build web page elements that can do many powerful things that normal, static web pages cannot. Active content is especially popular with advertisers who are always looking for new gimmicks to call attention to their product advertisements on web pages. Types of Active Content Not all active content is the same, however. Active content programs come in several different varieties. All of these different types of active content programs are created or built using different programming languages. Moreover, some of the programs are plain text programs (which you can actually read if you look at the HTML source code of a web page), while others are binary programs that are readable only by computers (they'll look like gobbledygook if you open them up and look at them yourself). There are three main types of active content programs that web browsers use:

Note: don't confuse Java applets with JavaScript -- though the names are similar, they're two different things. So, What's the Problem with Active Content? If active content can be used to build so many cool, fun things to go into web pages, why would anyone want to turn it off? There are several reasons:

Disabling Active Content All major web browsers allow you to turn these active content types on and off:

More Info If you'd like to learn a bit more about the various active content technologies that I discussed above, see these web pages:

And if you'd like to see some of the active content exploits that can be used against your browser, see the links here: Be careful, some of the "tests" at those sites may crash your browser or even your whole computer. |